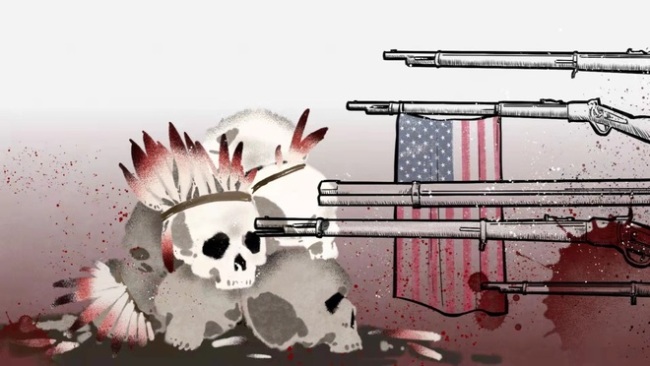

American Indian Wars: the roar of capital and a dirge of humanity

In the film Good Will Hunting, there was a scene when the protagonist Will Hunting was asked about reasons why he refused to work for the National Security Agency.

He replied, "Say I'm working at NSA. Somebody puts a code on my desk, something nobody else can break. So I take a shot at it and maybe I break it… But maybe that code was the location of some rebel army in North Africa or the Middle East. Once they have that location, they bomb the village where the rebels were hiding and 1,500 people I never had a problem with get killed. Now the politicians are saying, 'Send in the marines to secure the area'… It won't be their kid over there, getting shot… It'll be some kid from Southie taking shrapnel in the a*s… And the guy who put the shrapnel in his a*s got his old job, cause he'll work for 15 cents a day and no bathroom breaks. Meanwhile, he realizes the only reason he was over there in the first place was so we could install a government that would sell us oil at a good price. And of course the oil companies used the skirmish to scare up oil prices so they could turn a quick buck… So what did I think? I'm holding out for something better."

What he said was an accurate reflection of the giant web of interests woven by American political and capital powers through wars. It also expressed the frustration keenly felt by decent Americans of conscience over their own country's waging of wars.

History always repeats itself. Will's telling analysis of America's war logic also tells the fate of army officers who did not have the heart to draw their sword against innocent people in the genocide of American Indians.

On November 29, 1864, a 700-man force of the Third Colorado Cavalry under the command of Colonel John Chivington raided an Indian encampment, committing the blood-curdling Sand Creek Massacre. Chivington, once a Methodist pastor but now a butcher, shouted, "Damn any man who sympathizes with Indians! I have come to kill Indians, and believe it is right and honorable to use any means under God's heaven to kill Indians."

Under his instruction, more than 100 American Indians were killed, two thirds being defenseless women and children. Some victims were even dismembered, with their scalps and body organs treated as trophies by American soldiers. In spite of the ruthlessness, there were still a small number of compassionate officers in the army who refused to kill innocent people. Captain Silas Soule was one of them. His frustration-laden letters back then, now kept in the Denver Library, detailed the tragedy.

One letter written to Major Edward Wynkoop reads:

"The massacre lasted six or eight hours, and a good many Indians escaped. I tell you Ned it was hard to see little children on their knees have their brains beat out by men professing to be civilized. One squaw was wounded, and a fellow took a hatchet to finish her, and he cut one arm off, and held the other with one hand and dashed the hatchet through her brain."

In another letter to his mother, he wrote:

"The day you wrote, I was present at a Massacre of three hundred Indians mostly women and children. It was a horrible scene, and I would not let my Company fire. They were friendly and some of our soldiers were in their Camp at the time trading… Some of the Indians fought when they saw no chance of escape and killed twelve… of our men. I had one Horse shot… I hope the authorities at Washington will investigate the killing of those Indians. I think they will be apt to hoist some of our high officials. I would not fire on the Indians with my Co. and the Col. said he would have me cashiered, but he is out of the service before me and I think I stand better than he does in regard to his great Indian fight."